Ketchikan’s geographic isolation poses critical challenges in achieving language equity, a concept demanding that people of all linguistic backgrounds receive equitable access to educational resources, cultural validation, and institutional support. Recent interviews with students, educators, and community leaders reveal systemic failures and grassroots efforts to address these disparities.

Language equity transcends mere translation services; it requires dismantling systemic barriers that marginalize non-English speakers while affirming the value of linguistic diversity.

For Ketchikan’s multilingual learners, particularly its Filipino, Lingit, and immigrant community, this means access to curricula that leverage home languages as assets rather than deficits. Research underscores that equitable education for multilingual students hinges on “opportunity to learn,” which includes rigorous academic content paired with culturally responsive scaffolding.

THE ROLE OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNER (ELL) PROGRAMS

Effective ELL programs are pivotal. Albrim, a Ketchikan graduate, recalls how ELL staff in elementary school created a “safe space” that eased his language transition from Albanian to English. Such programs, when properly resourced, build foundational language skills while fostering cultural belonging.

Penny Hamlin, a former ELL teacher, emphasizes that robust programs require endorsed instructors, bilingual materials, and family engagement elements notably absent in Ketchikan’s current model. Yet, Ketchikan’s ELL infrastructure has eroded. In 2018, the high school offered five ELL classes staffed by certified teachers; today, students rely on a single study hall period and paraprofessionals lacking specialized training. This decline mirrors national trends where funding shortfalls and misprioritization exacerbate achievement gaps.

The Role of English Language Learner (ELL) Programs

Ketchikan’s school district supports 84 ELL students but falls just below the threshold for federal grant eligibility. Superintendent Robbins cites a 97% graduation rate among ELL students as proof of success, yet this metric obscures deeper issues.

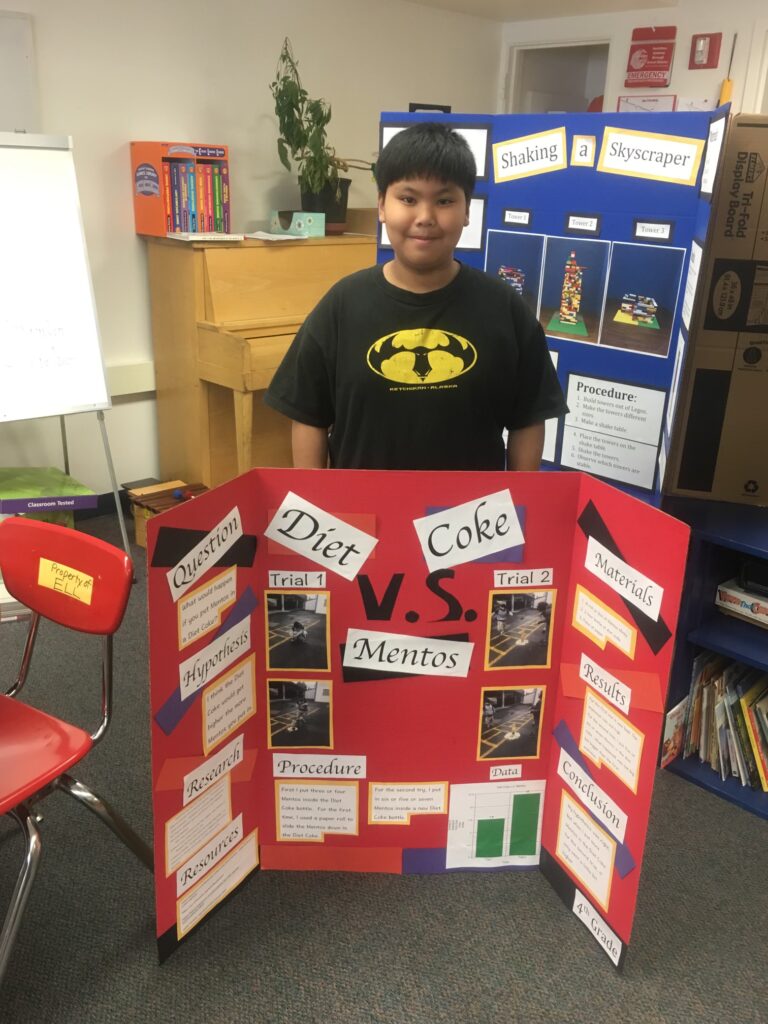

Dyl Colmenares, a Filipino immigrant, describes his middle school experience: no dedicated ELL teachers, limited bilingual resources, and reliance on peers to learn English. These gaps persist despite federal mandates requiring districts to identify and support ELL students within 30 days of enrollment.

Penny Hamlin attributes these failures to administrative neglect:”Without a champion for ELL, training for staff evaporates, and compliance with federal laws becomes optional.” The district’s reliance on untrained paraprofessionals at Tongass School of Arts and Sciences and Ketchikan Charter School further strains resources. Language inequity intersects with cultural dislocation.

Dave Ketah, a Lingít learner, highlights how historical policies forbidding Indigenous languages in schools created generational trauma. While Sealaska invests $10 million in Lingít revitalization, Ketchikan’s schools lack parallel initiatives. For Filipino students, the absence of Tagalog or Bisaya resources exacerbates isolation.

Czarina Cabillo, a Ketchikan High junior, notes that without ELL support, students “struggle silently,” compounding anxiety and academic disengagement.

Lessons from Sealaska, Kodiak, and National Models

Sealaska’s collaboration with the Juneau School District offers a blueprint for Ketchikan. By integrating Lingít into curricula and training Native language teachers, the initiative bridges cultural preservation and academic success. Joe Nelson, Sealaska’s board chair, argues that such efforts combat the “attainment gap” for Alaska Native students, who face disproportionate dropout rates post-high school.

Kodiak’s award-winning ELL program, praised for its family engagement and bilingual instruction, contrasts sharply with Ketchikan’s deficiencies. Nationally, districts adopting “language equity frameworks” report improved outcomes by:

- Validating home languages in curricula

- Training general educators in multilingual strategies

- Auditing resources for accessibility

Grassroots Advocacy & Action

Community members like Penny Hamlin are pushing for systemic reform. The ELL Task Force advocates for:

- Hiring endorsed ELL teachers

- Mandating cultural competency training for staff

- Restoring dedicated ELL classrooms

These measures align with research emphasizing that language justice in education requires “structural solutions” like equitable budgeting and antiracist policies.

Ketchikan’s struggles reflect broader national debates about educational equity in polarized times. Yet, its community’s resilience-from students like Dyl Colmenares mastering English through YouTube to advocates like Penny Hamlin demanding systemic change-offers hope. Ketchikan can model how rural communities honor linguistic diversity while fostering academic excellence by reimagining ELL programs as hubs of cultural vitality rather than remedial spaces. Research affirms that equity is not a zero-sum game; investing in multilingual learners enriches entire communities. The path forward requires courage, collaboration, and an unwavering commitment to justice–one word, one student, one policy at a time.

Sources

- “His Grandmother Was Forbidden to Speak Lingít in School. Now School Is Helping Him Reclaim It.” The 74 Million, 13 Oct. 2022, www.the74million.org/article/his-grandmother-was-forbidden-to-speak-lingit-in-school-now-school-is-helping-him-reclaim-it/.

- Twitchell, X̱’unei Lance A. Haa Dachx̱ánxʼi Sáani Kagéiyi Yís: Haa Yoo X̱ʼatángi Kei Naltseen [For Our Little Grandchildren: Language Revitalization Among the Tlingit]. University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2018, dspace.lib.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10790/4586/1/Twitchell_hilo.hawaii_1418E_10163.pdf.

- “Alaska Native Language Bibliography: Home.” University of Alaska Southeast, 5 June 2012, uas.alaska.libguides.com/c.php?g=281175.

- Worl, Lisa X’unyéil. “Cultural Integration – Native Language Gathering in Ketchikan.” Association of Alaska School Boards, 13 Jan. 2020, aasb.org/cultural-integration-native-language-gathering-in-ketchikan/.

- “Sealaska Partners to Support Education Equity in Alaska.” MySealaska, www.mysealaska.com/news/item/stories/sealaska-partners-to-support-education-equity-in-alaska/.

- “Our Native Legacy.” Ketchikan Story Project, ketchikanstories.com/film/our-native-legacy/history-and-heritage.

- “Revitalizing Indigenous Languages in Secondary School in Anchorage, Alaska.” University of San Francisco Scholarship Repository, 20 May 2021, repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1587&context=diss.

- “State of Alaska Digital Equity Plan.” Alaska Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development, 23 Jan. 2024, www.commerce.alaska.gov/web/Portals/19/pub/State%20of%20Alaska%20Digital%20Equity%20Plan%20–%20Final%20(R8c%2001-23-24).pdf.

Maraming Salamat to Rafael Bitanga, Malasakit Matters Feature Writer